Abenaki Contributions to Our Community - Mural Project

Richmond Town Center

Art is supposed to make you think!

Richmond is located within Ndakinna, the homeland of the Western Abenaki people. The land's original inhabitants still live here and form an inseparable part of our community and culture, having developed many technologies and traditions that Vermonters enjoy today. This mural seeks to celebrate that bond. It was painted by Richmond Racial Equity (RRE) group in partnership with the Vermont Abenaki Artists Association (VAAA). Abenaki artists Lisa Ainsworth Plourde, an accomplished painter with deep knowledge of native traditions, and Vera Longtoe Sheehan, the director of VAAA, served as consultants on this project.

Richmond is located within Ndakinna, the homeland of the Western Abenaki people, who have a unique connection to this land and have been its traditional caretakers since at least the last Ice Age. For hundreds of generations before the European colonists arrived and applied their own borders and labels, the Western Abenaki people lived and worked on this land, farming and harvesting resources without degrading the land's ecological health. This mural seeks to celebrate how the Western Abenaki people continue to form an inseparable and influential part of our community.

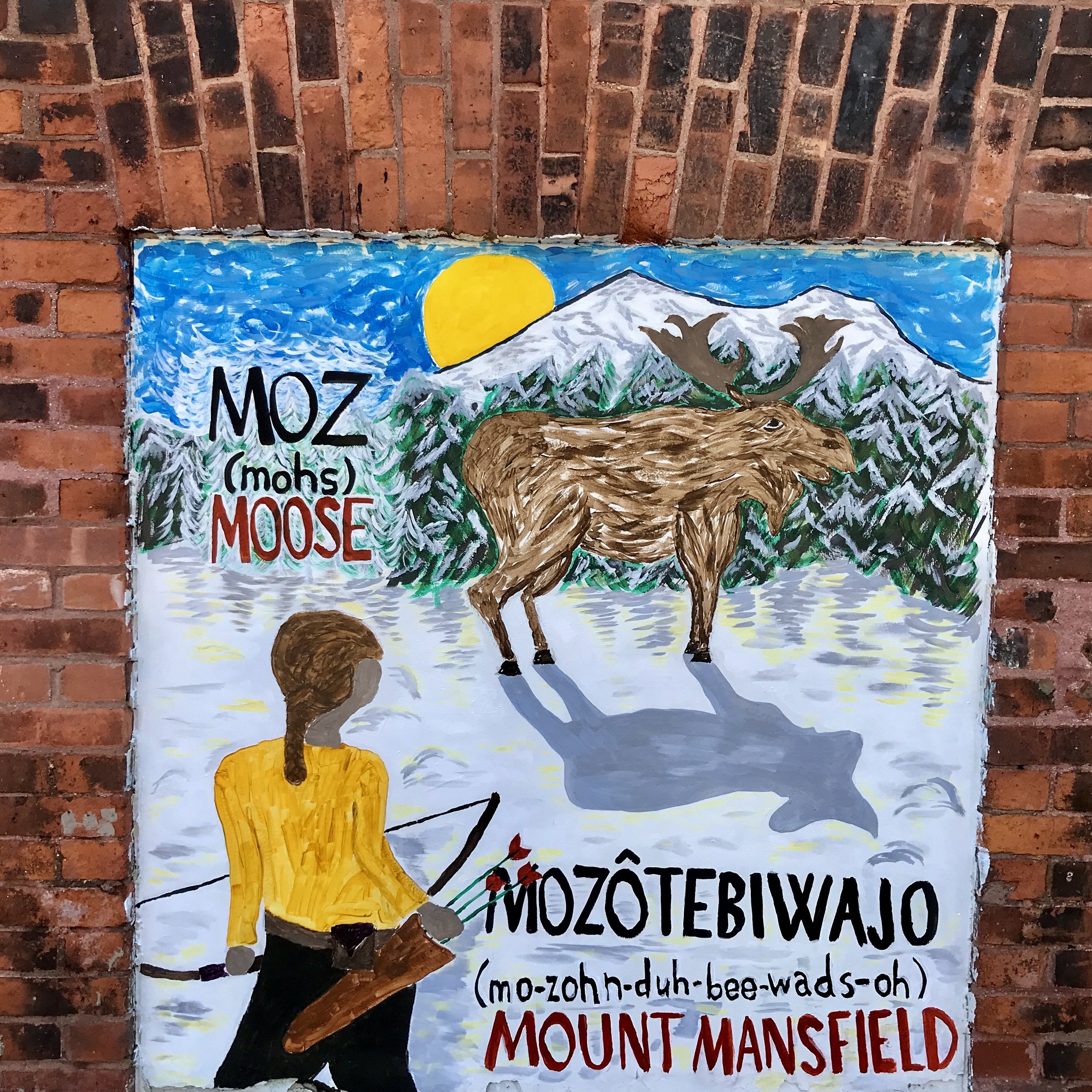

The Western Abenaki name for Mount Mansfield is Moose Head Mountain, Mozôtebiwajo. Early spring is the traditional moose hunting season with the month of March named for Mozokas, the moose hunt moon.

Northeastern Indigenous Peoples developed agriculture at least 4000 years ago, and mound gardens continue to be practiced by Indigenous gardeners. In addition to the Three Sisters of corn (skamôn), beans (adbakwa), and squash (wasawa), the Abenaki people have long cultivated four other plants: Jerusalem artichokes, sunflowers, ground cherries, and tobacco. This heritage is symbolized by the Seven Sisters constellation.

The Abenaki people taught European settlers how to tap sugar maples with a hardwood spout, collect the sap in a birchbark bucket, and boil it over a fire to produce maple sugar products. Today many Abenaki people continue to collect maple sap using modern aluminum buckets.

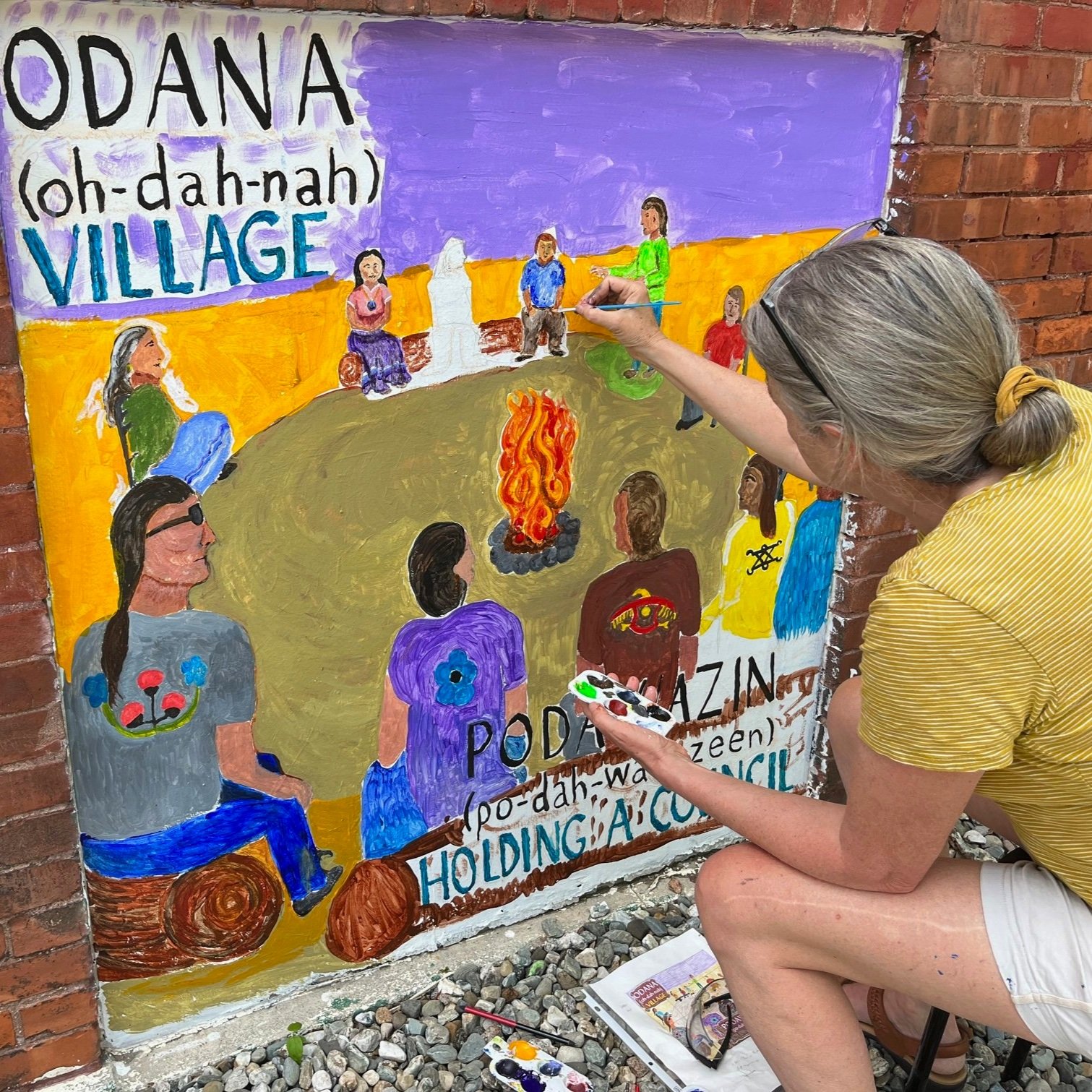

Democratic ideals, concepts of social equity, and aspirations for personal freedoms were planted in the minds and hearts of the early settlers by the example of the Indigenous people here, who made decisions by consensus, practiced egalitarianism, and often challenged the settlers about their social hierarchies and forms of oppressions in public debates.

The Western Abenaki language is a descriptive language, based on root words specifying physical qualities. Thus the region’s largest river is Winoskisibo: Winos means onion, ki means land, and sibo means river. Ramps and other wild onions grow in abundance along its shores.

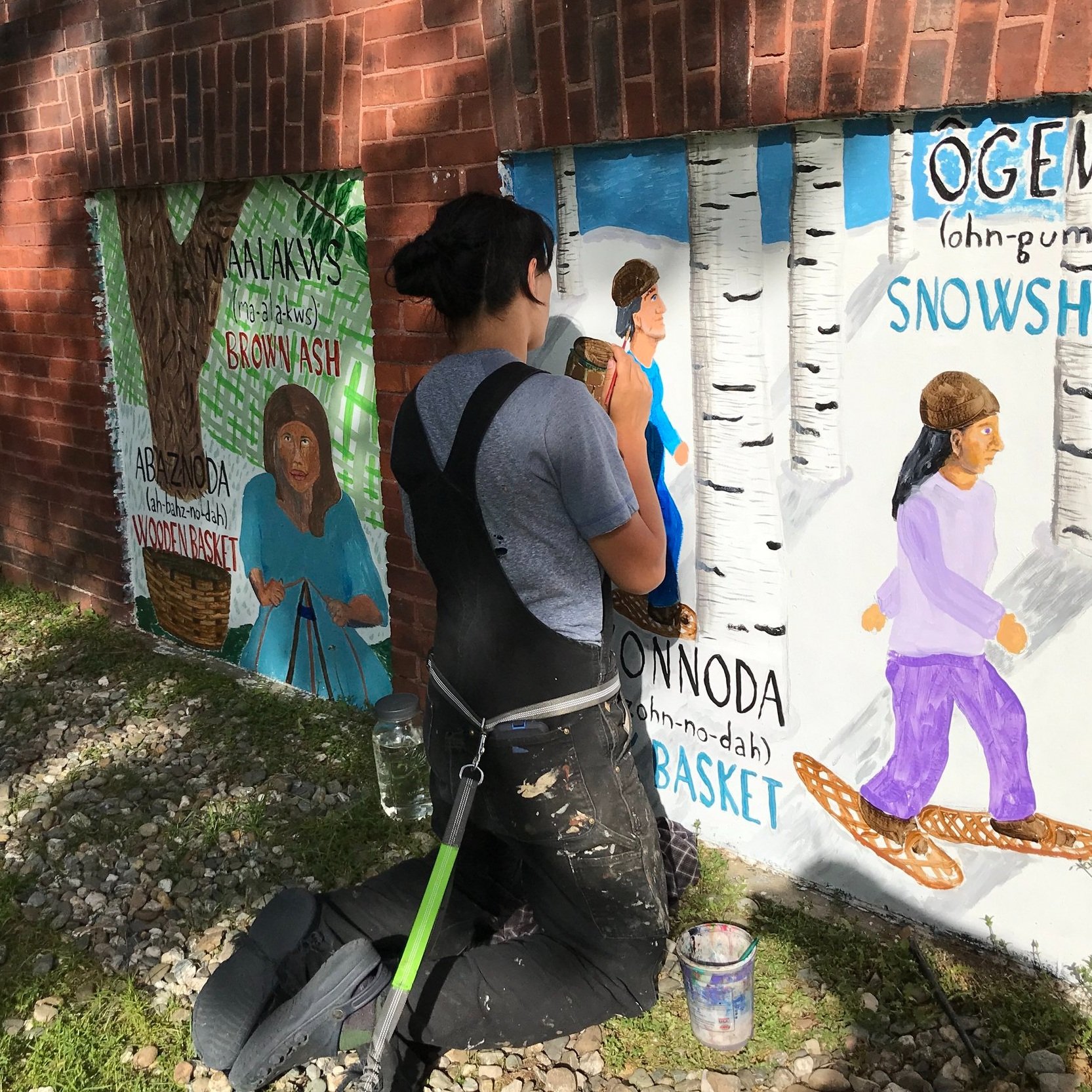

Known as the “basket tree,” the brown ash is considered sacred to many of the Indigenous peoples of the northeast, and figures prominently in the Abenaki creation story. The wood is both strong and flexible, making it particularly well suited for weaving durable containers. The emerald ash borer threatens the long-term survival of this critical tree.

From The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation by Frederick Wiseman: “We Alnôbak [the Abenaki people] and our neighbors made a teardrop-shaped snowshoe that is the prototype of the modern snowshoe used by winter backpackers and campers... No one is sure how many years ago or where in North America this wonderful invention was developed, but early colonial records contain numerous references to Abenaki snowshoes." Woven pack baskets, still made today, can carry almost anything (including items too tall to fit in a backpack) and are easy to load and unload.

Birch bark (wigwa) forms the basis of the traditional canoe (wigwaol), which was invented by the Abenaki people and is nearly identical in form to modern wooden and fiberglass models. This panel celebrates the importance of the Winooski River corridor as a travel route and source of food, medicines, and fibers, and where much Abenaki life was centered.

Traditionally, the Abenaki people would selectively burn sections of forest; the resulting parkland promoted abundant wildlife and hosted wild blueberries, which were gathered and enjoyed as they are today. The Western Abenaki language has several names for Camel’s Hump, one being Saddle Mountain, Tawabotiiwajo.

Show your support for this artwork by donating to the Vermont Abenaki Artists Association!

Vermont Abenaki Artists Association is a Native American arts organization that serves the public by connecting them to Abenaki educators, artists from the visual and performing arts as well as literary genres. VAAA’s mission is to promote awareness of state-recognized Abenaki artists and their art, to provide an organized central place to share creative ideas, and to have a method for the public to find and engage state-recognized Abenaki artists. Please consider supporting their ongoing work with a donation below.

Richmond Racial Equity Group

RRE seeks to engage the Richmond community in opposing racism – and advancing equity for Indigenous, Black, and people of color – through education, policy change, and reparations. Over the last two years, RRE has been in dialogue with Abenaki tribal leaders, culture bearers, and language experts to develop a land acknowledgment for the town of Richmond, and to explore ways to honor that acknowledgment through easements, cultural and historical markers, and celebrations. RRE is an ad-hoc group of Richmond and nearby residents; everyone is welcome to join.

The artists hard at work!

The mural was sketched out and painted by many: Scott, Judy, Darcie, Ryan, Gioia, Sophie, Leslie, Dave, Rebecca, Grace, Jed, Ben, Cali, Wafic, Patty, Gretchen, Alexis, Peggy, Dixie, Abby, Mae, Ingrid, Veronique, Francesca, and Sau. We thank artist consultants Lisa Ainsworth Plourde and Vera Longtoe Sheehan for their tireless review to ensure cultural accuracy. Without them this work would not have been possible.